Passive investing has created a vast valuation gap across the global capital markets. This phenomenon has generated opportunities for active investors, particularly those who still believe in the idea that what you pay for an asset matters to your expected return.

The most obvious example is the “Magnificent Seven” stocks that have accounted for a massive share of return and risk in the equity market. Yet even the “Normal 493,” which exist in the shadow of the seven mega-cap names, hold outsized portions of our aggregate equity allocation.

Unseen from passive allocations—and often under-owned—are thousands of companies that, for lack of size or for their being outside of a “sustainable” industry, are left out of flows driven largely by market capitalization.

If correctly filtered and carefully combined, security selection of these unloved stocks can be a significant source of Alpha. I believe that this is in addition to the SMB (small minus big) Fama/French stock pricing model that predicts that smaller companies outperform larger ones over the long-term[1].

Hedge fund and Value investor David Einhorn recently told Bloomberg:

“The markets are fundamentally broken…value is just not a consideration for most investment money that’s out there. There’s all the machine money and algorithmic money, which doesn’t have an opinion about value, it has an opinion about price.”[2]

Passive>Active

How much “machine money” is there? Passive allocations have grown over the last forty years from zero to roughly 50% of equity investments. Today, more than 90% of Target Date investments go straight to passive investments, and 401(k) participants rarely transact. It’s “set and forget,” and investors of all types and sizes have benefitted from passive’s ease of use and across-the-board cheapness.

According to Morningstar’s latest U.S. Fund Flows data[3], passive funds and ETFs now have $14.3 trillion across all asset classes, in contrast with $14.1 trillion in active funds and ETFs. The spectacular success of passive looms large in the capital markets.

Michael Green describes the effects of passive in his post The Greatest Story Ever Sold:[4]

“With passive, the diseconomies manifest as a Ponzi-esque transfer of wealth from future generations of investors to current generations rather than deteriorating performance.”

While the Ponzi allegation may be hyperbole—after all, the Mag 7 have actual earnings and commercial moats—we believe that the market, driven by passive, has created room for what Octane calls structural alpha. Although we didn’t invent the term, it describes how you can reduce concentration risk to the market without necessarily sacrificing returns. (By market we mean the cap-weighted passive indices.)

We agree with Mssrs. Einhorn and Green that market dynamics have been permanently altered. The risk now embedded from over-concentration should give all allocators pause. There is zero discretion in passive mandates, so net flows direct all the buying and selling, and any discretionary capital “betting” on fundamentals have been overwhelmed by this force. (Ask any retired Value manager!)

Good News for Widget Investors

The good news is that you don’t need to love or hate indexing to use it to your advantage. Let’s find an example of what I do every day at Octane. Here is a large and well-capitalized company in the widget industry, that happens to be an integrated conglomerate:

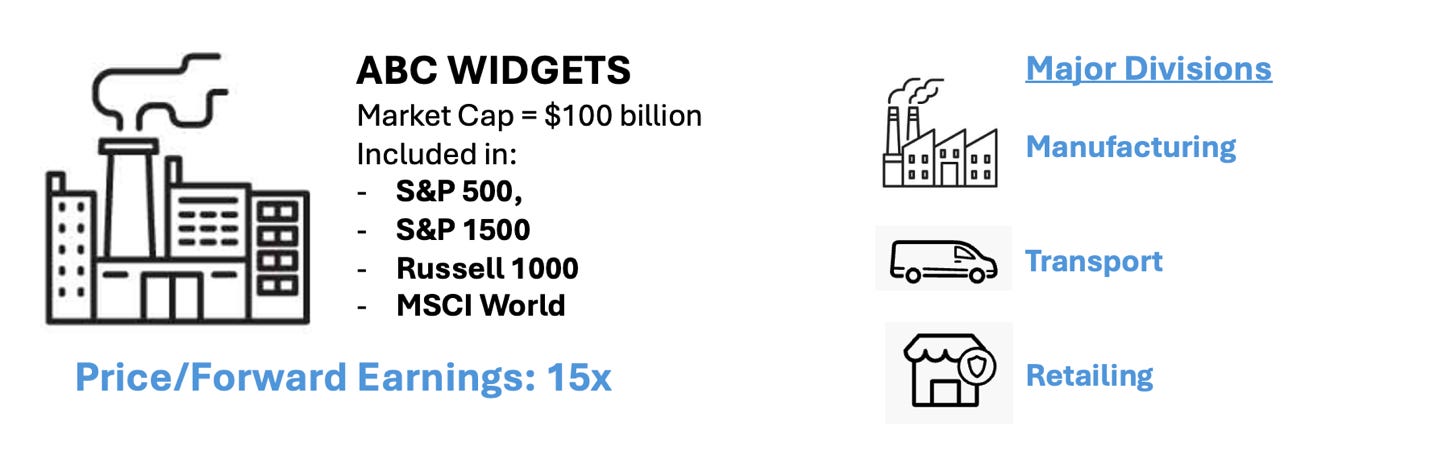

Here we have the world-famous, mega-cap name ABC Widgets, which, because of its size, is in every meaningful equity index. Since investors around the world buy it automatically in their passive allocations, it trades at a premium to the rest of its sector[5].

So when Mrs. Smith adds $120 to her Target Date fund each month, she owns a little more ABC Widgets. Same when a German pension wants cheap Beta exposure to global or to U.S. equities. The Germans get more ABC Widget stock, and if these flows make it more expensive, the next buyer will pay even more. That’s pretty much how it works, and the converse is true with redemptions and retirement decumulations.

Luckily for widget consumers everywhere, ABC does not have a monopoly on widgets. And as any business major or budding economist knows, there aren’t any moats or intellectual property rights around making and selling widgets.

So the market gives us the opportunity to construct a portfolio of similar economic and financial exposures through a number of smaller businesses; many of these are off the mega-cap index radar.

Let’s look at our fanciful world of widgets, and see what the market offers across three separate divisions that make up the conglomerate ABC Widgets: manufacturing, transport, and retailing.

Lo, our stock market gives us opportunities to invest separately across the three sub-sectors, to replicate the financial exposure to ABC Widgets.

Choosing XYZ Manufacturing, RAPID Transport, and Real Retail could in theory give us the same economic exposures at a steep discount to ABC Widgets, which has a P/E ratio of 15x. In this example, the P/E discount is over 50%, given an equally-weighted portfolio in the smaller names.

How would you build a portfolio by combining sub-sector companies? One way is to look at the market with an All-Cap Value lens.

This allows us to sort through the names and allocate to companies whose financial metrics like free cash flow look the most promising. Another reason to see the industry from an All-Cap Value lens is to invest in cheaper foreign conglomerates via ADRs. Foreign companies that trade on U.S. exchanges can command discounts for any number of reasons; often it’s their exclusion from the S&P 500 that keeps them cheap.

Using a Value approach to the sub-sectors also allows us to lean into cheaper components when their valuations are more compressed, for example, taking profits when the manufacturing sector is strong, and reinvesting into a sector that has lagged. As long as idiosyncratic and sector risk is managed, this can be a version of selling high and buying low across the widget industry.

Finally, this note would be incomplete if we left out the Palo Alto Widget Accord, which proclaims that society needs to ban widgets, because they are used too often in banal examples in college textbooks(!)

We calculate that the global widget divestment movement now includes $20 trillion of capital. So even grand old ABC Widgets trades at a discount to its larger-cap peers that are not in the widget business. Again, a Value lens helps us sort the risk/reward as we look to the broader market to diversify the portfolio and mitigate concentration risk.

As the Wall Street adage goes, passive investing is like a knife: it can be used to stab someone or to cut butter. Whichever way you think of passive investing, try to hold it by the handle, and not the blade.

[1] For a really cool dataset on SMB and other factors, visit AQR’s Website.

[3] https://www.morningstar.com/lp/fund-flows-direct

[5] Passive investment flows are not the only reason for this fictitious company to trade at a premium. ABC Widgets should also give comfort to investors who are willing to pay a premium for its status as an integrated widget player, for its potentially strong balance sheet and access to funding, and other micro-economic benefits of scale, for example, integrated SG&A expenses and potentially superior purchasing power.

Good post!

lol this David Einhorn interview did the rounds in our office here too. great article.